Positionality and Change: An Inquiry on Leadership Approaches

Throughout this process, I have been struck by the opacity of the roles we play in independent schools and how that positionality informs our access to information and people, the integrity of our work, and the level of engagement with others. Reflecting on the early challenges in identifying a topic for the practicum, there are three main takeaways.

Curiosity and inquiry are always welcome, but to some extent the context of the practicum and study created a sense of encroachment. I wonder if all schools are like this and if the collaborative engagement across disciplines, departments, and roles can be more fluid and organic. As someone who wears many hats and has many identities in the school community, my lens and perspective is unique. However, what I have learned is that it is not so much the identity or perspective that I choose to use at any given moment, but that it is defined by the people I interact with. My history, relationship, connection, and hierarchical position in the school all play important roles in defining these interactions.

I recall some years ago while on a DEI committee, the upper school director at the time asked me if their presence in the meeting affected the tone and work of the group. I shared that it certainly shouldn’t but that it probably did. And proof came as we were starting one meeting and the conversation was robust and more open than usual. When she came in, the tone immediately shifted to a more measured level. She and I connected afterwards and reflected on this nuance and accepted that our positionality played a critical role in defining the openness of engagement and work.

In a similar context, some years ago, the head of school and I joined a staff affinity group meeting during one of our professional development days. We did so in solidarity with our staff to show our support, but we would later hear that this was viewed negatively as an encroachment to the space and inhibited some from speaking freely. Our unintended position of power and authority impacted our ability to engage with them as peers and stifled their ability to be their authentic selves. How they perceived us in our positions defined our identity in this space and created a challenge for open dialog.

I use these two examples as illustrations of the ways in which positionality can play a role in working with and affecting change in our institutions. The unintended consequences of our authority or perceived position of power can create resistance and resentment in certain situations. How can we rewire and create a more open and inclusive culture where positionality does not affect the ability for a community or organization to move forward and change?

Positional Leadership

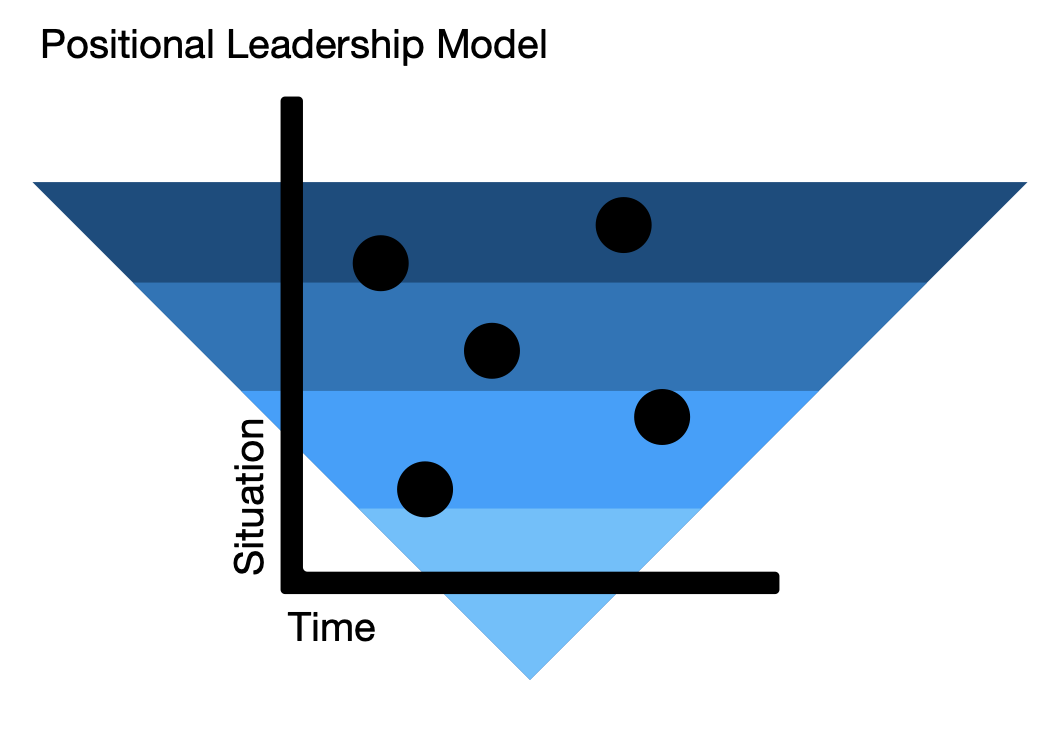

I recently presented at the Association for Technology Leaders in Independent Schools (ATLIS) conference on the topic “Fostering a Culture of Empowerment to Enhance Recruitment, Retention, and Belonging” and in my talk shared a modified concept of servant leadership, called “positional leadership” and the inverse pyramid model. This model shows the leader at the bottom of an inverted pyramid. However, this positional leadership model allows for the rotation of who is in that position of leadership given the situation, task, or challenge over time.

This model helps change the position and power of leadership and shifts it to one where empowerment of others creates agency and belonging and a more open culture of trust. The ability for us to elicit change in our schools as leaders hinges on our ability to create the context and culture of trust. Finding pathways and frameworks for this are essential. Some examples include:

Transparent decision making - Creating open avenues of communication and connection, articulating the reasoning and process along the path of decision making.

Growth mindsets - Encouraging and embracing mistakes and failures as avenues of growth and the vision to reframe oneself and contribute meaningfully.

Inclusive open door policies - The door may be open, but how can we bridge relationships in ways that encourage and enable the entering of spaces of authority.

Equitable Acknowledgement - Consistently ensuring that all members of your organization are recognized for their contributions.

Modeled accountability - Owning and modeling being accountable to the people we serve and leading by example. Showing vulnerability, humility, and empathy.

For the purposes of this report, one of these frameworks rises to the level of broad relevance. In his podcast, Remarkable People, Guy Kawasaki interviews Carol Dweck, author of Growth Mindset. This episode highlights a pivotal aspect of leadership that is subsequently one of the key anchors of Kawaski’s latest book, Think Remarkable. Carol Dweck shares,

“In our research, we saw some people favored more of a fixed mindset, the idea that you have a certain amount of intelligence or any attribute, and that's it, that's who you are. You're lucky or you're unlucky. Case closed. Other people tend more toward the belief, ‘Hey, you have abilities, that they're capable of development.’ You can grow them and expand them through taking on challenges and sticking to them by trying the strategies, by getting lots of input and help and mentorship.

“We found over time that it made a big difference. People who had more or endorsed more of a growth mindset, they took on those challenges. They wanted to grow those abilities, those in more of a fixed mindset. So the challenge is threatening. Maybe I'll be unmasked as an imposter. Maybe I'll find out I'm no good.

“They also gave up quickly ... The fixed mindset, they also gave up quickly because they saw mistakes and setbacks as meaning they didn't have ability. In a growth mindset, welcome to learning. There are mistakes, there are setbacks, and you align them for what you can learn and how you can move forward more effectively. So that's the basic idea.

“Again, in our research, we showed it predicted some long-term outcomes. We developed short programs for students to change their mindset and we saw it helped them do better in school, especially the lower achieving students, low income students, students from underrepresented groups that flourished more under the growth mindset.

“Then the first big thing we learned was that it's not that you have one mindset or the other. We fluctuate. We can be mostly in a growth mindset but have a big setback, ‘Whoa,’ outcomes that are fixed mindset or social comparison. Oh, my God, that is the scourge of our current civilization. Social media forces you to compare yourself to others, forces you to seek as many likes as possible.

“Whatever you put out there, you're on the line. Is anyone going to like it? How many people are going to like it? So those kinds of experiences, even if we're mostly in a growth mindset a lot of the time, can trigger us into a fixed mindset, and we kind of have to find our way back.

“We have to kind of talk to that fixed mindset, say, ‘Thank you very much. I assure you; I know you're trying to protect me, but I'd like you to hop on board with my growth mindset plan and over time make friends with it, harness its energy, and bring it along with you. Don't try to squelch it, that won't work,’ but the other really big thing we found is mindsets are not a loan enterprise.

“It's not like you have your growth mindset and you take it with you and you are challenge-seeking and resilient. The environment you're in matters hugely. “

This passage of the podcast makes me think about the ways in which we foster these mindsets situationally with not only our students, but the faculty and staff we work with. How can we foster this sense of risk taking, challenge, and vision of oneself and create a sense of courage and authenticity without judgment and with limitless possibilities?

Looking at my own team and how we’ve managed growth and change throughout the years, a key aspect of this is guiding them in envisioning themselves in different situations and roles, and encouraging them to take the leap to take on those roles. Providing an ethos and environment where people can both identify with the job they have and identify with the dimensional contributions they would like to make outside of their spheres of influence. This culture to some extent is prevalent in independent schools and is more commonly referred to as “wearing many hats.” Within my team, each member voluntarily contributes to the school's programs. From coaching eSports and robotics teams, to venturing out on outdoor education trips, to coaching cross country and aquatics sports, and teaching and advising, the breadth and depth of our engagement is a model for connecting individuals and their unique talents and interests to the school and its students.

For the students, this plays a critical role in fostering academic and social growth. Identifying with their academic performance or social standing as a measure of their belonging and their ability to change and grow over time can be critical in students envisioning themselves and their potential. We will revisit this concept in the context of STEM and the power of belonging later in this report.

The same hesitation and anxiety associated with the social media example she provides can be seen in some people’s approach to stepping out of their jobs and contributing to the community and organization. “Will they accept me? Do my opinions matter? What can I do from my role?” So how can we cultivate this sense of courage, risk taking, and growth? Dweck goes on to say,

“So organizations too, the idea that everyone has something valuable to contribute and everyone is capable of growth. To see that in action is amazing, but again, the policies are about developing, not just choosing the high potential people and giving them the opportunities. It's about committing resources to everyone.”

The process of the practicum and study itself provided a revelatory opportunity to think about and consider the processes, nuances, and social and organizational dynamics of institutional change in independent schools. My position as the director of technology elicited an unconscious and system bias and framing of the scope of this study. The paradigms of voice, and where contributions are recognized, define our identities and scope of engagement at our schools. As a multifaceted member of the community, this has always been a challenge for me in navigating administrative structures and my self worth and value. Seeking validation in areas outside of my immediate sphere of influence has been a career long effort. Reframing who we are, what we can contribute, and where we can have a voice is an organizational and community construct that, if broken down, can provide unique opportunities for innovation and ideas. We encourage an agency for reinvention in our students. How might this philosophy of approach applied to our faculty and staff help our organizations be more nimble and forward thinking?